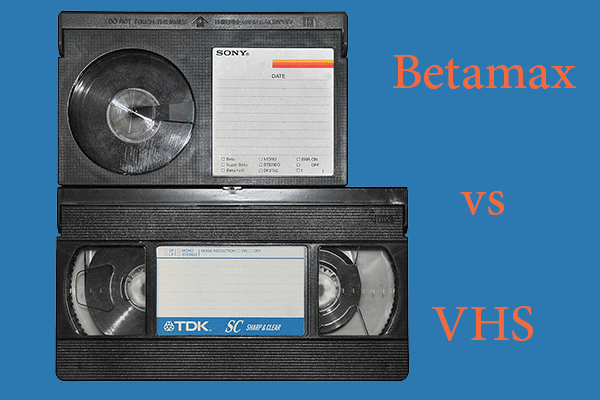

It was Tokyo, 1975. Rain pelted against the windows of a conference room at Sony headquarters as inside, the inventor of the legendary “Walkman”, engineer Nobutoshi Kihara, held a small, shiny video cassette in his hand—Betamax. A technical marvel: razor-sharp images, stable tape running, compact dimensions. For Sony, it was more than just a new product. It was the future and, after the Walkman, another technical masterpiece from Sony.

Kihara and the whole of Sony were convinced that Betamax would revolutionize home cinema. The press celebrated the system, experts praised its quality. Sony had delivered – as always. But something was stirring in the shadow of the giant.

While Sony focused on technical brilliance, in a less ostentatious office building, a small group of engineers at Japan Victor Company (JVC) was working on a device that did not seek to adorn itself with glory. Their solution was less elegant technically, the cassettes were larger, and the image was grainier, but this allowed the system to record for longer periods of time.

At the helm of this project was a man whom hardly anyone knew; Shizuo Takano. A man who preferred to observe rather than explain. His eyes were dark, his voice calm, almost monotonous. But his imagination was not that of an engineer alone.

The JVC board was divided when Takano presented his version. His video cassette was expensive to develop, full of teething problems, and its market potential was considered extremely low. Sony was simply too powerful, too established after the economic success of the Walkman. Quite a few members of the JVC board demanded that

the project be abandoned. However, Takano had not only developed a video cassette, but he also had an idea of how to beat Sony and Betamax.

At the decisive meeting, Takano proposed a strategy that had never been seen before and was considered economic suicide by the JVC board. “You’re giving away our development crown,” shouted one of the board members, to which Takano replied: “Sometimes you have to share a crown to build a kingdom.”

The decision in Takano’s favour was made late at night, and the consequences of this would have a fundamental impact for JVC, Sony and the entire industry.

A few months later in the spring of 1976, a small group of leading managers from Panasonic, Hitachi, Sharp, and Toshiba received an inconspicuous, almost secret invitation from JVC. This small, hand-picked circle of leading competitors did not know why they had been invited to such an unusual meeting.

When Takano stepped in front of the audience, he and his company had a lot to lose and even more to gain. He presented JVC’s Video Home System technology for the first time, demonstrating its longer recording time, solid mechanics, and disadvantages compared to Sony’s latest Betamax system—and then he laid his cards on the table.

“We all know that Sony has a technically superior product to JVC. And for this reason, we have decided to change our distribution strategy. Instead of focusing on exclusivity in technology like Sony, we will give each of you full technical insight into our technology, empowering you to replicate our technology under your own name free of charge. The only thing you have to pay is a license fee on every device and every Video Home System (VHS)cassette produced with VHS technology.”

The guests were amazed.

A promise that every competitor could use VHS technology and build devices under their own name was risky for JVC and revolutionary for the industry. No brand specifications. No dependencies. Just VHS as the common standard. There had never been anything like it before. And yet, those present immediately recognized the significance. Instead of blocking each other in competition, they could build a market together—against Sony, the primus maximus.

The license fees were set strategically high enough to cover development costs and secure a profit, but low enough not to be a barrier to market entry. JVC did not want a dominant position – they wanted market penetration with the aim of getting as many manufacturers as possible to make VHS the standard. Thus, an industry secret became an open offer – in a world accustomed to keeping everything under wraps, and this because JVC understood what Sony overlooked: sharing can multiply.

While Sony stuck to its exclusive Betamax strategy, the VHS market exploded. The devices became cheaper, and the selection grew. Every department store now had dozens of models – all with VHS technology. Customers could compare, choose, and negotiate. And they did – in droves.

SONY was technically better, but JVC was strategically smarter.

JVC’s plan was anything but naive from an economic standpoint, as a small percentage of each unit sold went back to JVC and profits mounted VHS became the most widely used video technology worldwide—and JVC profited without bearing the entire burden of production. By the end of 1980, JVC’s market share was over 95% (!) and was only replaced in the mid-1990s by the technical revolution of DVDs.

Sony, on the other hand, remained true to its strategy for a very long time. They produced alone, controlled the entire process – but limited themselves, and by the time Sony realized its mistake, it was too late.

What had begun as a risky experiment became one of the greatest successes in the history of technology. Not because VHS was technically superior – but because it was a clever strategy that compensated for the technical disadvantages.

For Shizuo Takano, it was not a victory over Sony. A win beyond thinking outside the box – proof that control isn’t all that matters.

Giving up control is not always easy, especially when it comes to one’s own assets in the private sphere to establishing a personal trust structure or similar.

With over 20 years in the trust business, we at Carey Zurich know the ins and outs of trusteeship. We are committed to serving the needs of trusts and their beneficiaries, foundations, and companies with Swiss-level thoroughness and reliability, as well as the innovation, creativity, and excellence you expect – because we care(y).

At CAREY ZURICH, we are specialist in setting up and managing advantageous structures for our customers and we would be pleased to establish a private structure in the form of a company, trust, foundation or whatever is suitable. We are committed to serving the needs of our customers with all the Swiss thoroughness and reliability that you would expect, because we care(y).